Penistone Railway Works has officially been open for less than a month and today I made my first sale! At 10:02 this morning someone bought a spark arrestor for the L&YR "Pug". If you go back through Shapeways live feed you might still be able to see the sale for yourself -- if not you'll have to trust that I didn't doctor the screenshot.

In a way I'm really happy that the first item I sold was a spark arrestor as this is the object that initially got me interested in 3D printing, and which led to me setting up Penistone Railway Works.

Now I know one sale doesn't make a successful shop but it's a start.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Sunday, January 27, 2013

3D Modelling In 3D

Since the test print of my coal wagon arrived a few days ago I've spent some time improving the 3D model in order to correct some of the outstanding issues with it. Unfortunately as I've added new features to the model I've run into a few problems.

Essentially the model is constructed in Blender by adding a large number of components together via a combination of boolean, array and mirror modifiers (they all do what you would expect given their names). One problem is that sometimes the boolean modifiers don't seem to do what you would expect (on occasions a union seems to have the effect you would expect from a difference modifier). I'm not sure what the problem is (it isn't inverted normals), but it means that I've had to move away from merging every part into a single object. This isn't a problem as Shapeways will accept files that contain multiple overlapping objects and print them as a single shape. Experience, however, shows that sometimes Shapeways gets confused, as an uploaded model will look completely wrong in the generated preview image.

The solution to "fix" such models seems to be netfabb Studio Basic. I'm not going to go into any details on how to use netfabb as there is already a good tutorial, instead I thought I'd show you one of the fun side effects; it can generate anaglyph images.

Once you have loaded your object file into netfabb, you simply right click on the object and from the Extras menu choose Stereographic View. The image above uses the standard red-cyan colouring. If you've read any of my other blogs (see here, here, here, and here) then you'll know I have an interest in 3D images/photos even if most of the people who read my blogs can't see them for one reason or another. Anyway, not only is it fun to play with this view in netfabb, but it actually gives you a much better sense of the object you are modelling than just viewing the 2D rendering in Blender; it's almost as if you are holding the item in your hand!

Essentially the model is constructed in Blender by adding a large number of components together via a combination of boolean, array and mirror modifiers (they all do what you would expect given their names). One problem is that sometimes the boolean modifiers don't seem to do what you would expect (on occasions a union seems to have the effect you would expect from a difference modifier). I'm not sure what the problem is (it isn't inverted normals), but it means that I've had to move away from merging every part into a single object. This isn't a problem as Shapeways will accept files that contain multiple overlapping objects and print them as a single shape. Experience, however, shows that sometimes Shapeways gets confused, as an uploaded model will look completely wrong in the generated preview image.

The solution to "fix" such models seems to be netfabb Studio Basic. I'm not going to go into any details on how to use netfabb as there is already a good tutorial, instead I thought I'd show you one of the fun side effects; it can generate anaglyph images.

Once you have loaded your object file into netfabb, you simply right click on the object and from the Extras menu choose Stereographic View. The image above uses the standard red-cyan colouring. If you've read any of my other blogs (see here, here, here, and here) then you'll know I have an interest in 3D images/photos even if most of the people who read my blogs can't see them for one reason or another. Anyway, not only is it fun to play with this view in netfabb, but it actually gives you a much better sense of the object you are modelling than just viewing the 2D rendering in Blender; it's almost as if you are holding the item in your hand!

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Fencing From Just €0.15 A Metre!

As I mentioned in a previous post, when I place an order with Shapeways for 3D printed items, the order usually contains a number of items. The last order, as well as containing the test print of the 7 plank wagon, contained a new item to add to the range available through Penistone Railway Works: concrete fence posts.

So far the items I've designed for Penistone Railway Works have all been based off photos or measurements made by other people. Whilst this makes life easy, I decided that I wanted to try modelling something from scratch. When I walk to the train station one thing I pass a lot of are concrete fence posts. There are actually quite a few different designs that vary in height and shape. I might, in the future, model some of the other forms, but for now I'm focusing on the 5 foot tall posts. I chose these for two reasons; firstly they aren't just square posts, and secondly they contain a braced variant giving me something extra to model.

So on a cold day at the end of November last year (when on the way to the shops to buy lunch) I took a tape measure, a camera, a notepad, and a pencil and set out to take detailed measurements of the two fence posts. Whilst I did get a few funny looks from people walking past, I came home with copious drawings (not very good ones) and lots of helpful measurements.

After refreshing my memory of trigonometry I proceeded to turn the measurements into a 3D model. Fortunately for a shape as relatively simple as a fence post this isn't actually very difficult. The most difficult decisions relate to balancing a desire to produce an accurate model with producing a model that can be both printed and is useful. Hopefully I've managed to achieve that balance with this model.

Because printing a single fence post seems rather daft, I've actually strung 21 normal fence posts together on a simple sprue. The sprue isn't, however, simply waste plastic as I've added holes to it that act as a guide for drilling 1mm holes for the fence posts at the suggested distance apart (5cm on the model which matches the average real life spacing between posts). Given the recommended distance between posts, this means a single sprue will allow you to build a fence a metre long on your model; which at a scale of 1/76 results in being able to model 76 metres of fence. At the current price for printing this equates to approximately €0.15 to model a metre of real fencing.

The second sprue contains four of the braced posts, and again contains guide holes, this time for drilling the extra hole needed for the braced leg. These posts are needed where a fence ends or where it turns a sharp corner; a sharp corner usually consists of two fences ending at the some place.

Having now handled the test print, and checked that I can actually thread wire (I'm recommending 0.125mm enammeld copper wire from Maplin) through the holes, I'm really happy with how they've turned out. At some point I'll actually fit them to a test track so I can take a photo of them "in use". Given that I'm happy with how they've turned out they are now available from Penistone Railway Works, so if you should be in need of 4mm to the foot scale concrete fence posts you know where to go!

So far the items I've designed for Penistone Railway Works have all been based off photos or measurements made by other people. Whilst this makes life easy, I decided that I wanted to try modelling something from scratch. When I walk to the train station one thing I pass a lot of are concrete fence posts. There are actually quite a few different designs that vary in height and shape. I might, in the future, model some of the other forms, but for now I'm focusing on the 5 foot tall posts. I chose these for two reasons; firstly they aren't just square posts, and secondly they contain a braced variant giving me something extra to model.

So on a cold day at the end of November last year (when on the way to the shops to buy lunch) I took a tape measure, a camera, a notepad, and a pencil and set out to take detailed measurements of the two fence posts. Whilst I did get a few funny looks from people walking past, I came home with copious drawings (not very good ones) and lots of helpful measurements.

After refreshing my memory of trigonometry I proceeded to turn the measurements into a 3D model. Fortunately for a shape as relatively simple as a fence post this isn't actually very difficult. The most difficult decisions relate to balancing a desire to produce an accurate model with producing a model that can be both printed and is useful. Hopefully I've managed to achieve that balance with this model.

Because printing a single fence post seems rather daft, I've actually strung 21 normal fence posts together on a simple sprue. The sprue isn't, however, simply waste plastic as I've added holes to it that act as a guide for drilling 1mm holes for the fence posts at the suggested distance apart (5cm on the model which matches the average real life spacing between posts). Given the recommended distance between posts, this means a single sprue will allow you to build a fence a metre long on your model; which at a scale of 1/76 results in being able to model 76 metres of fence. At the current price for printing this equates to approximately €0.15 to model a metre of real fencing.

The second sprue contains four of the braced posts, and again contains guide holes, this time for drilling the extra hole needed for the braced leg. These posts are needed where a fence ends or where it turns a sharp corner; a sharp corner usually consists of two fences ending at the some place.

Having now handled the test print, and checked that I can actually thread wire (I'm recommending 0.125mm enammeld copper wire from Maplin) through the holes, I'm really happy with how they've turned out. At some point I'll actually fit them to a test track so I can take a photo of them "in use". Given that I'm happy with how they've turned out they are now available from Penistone Railway Works, so if you should be in need of 4mm to the foot scale concrete fence posts you know where to go!

Thursday, January 24, 2013

A Printed Wagon: Take 2

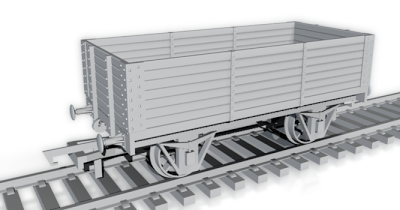

So having learnt a number of lessons from printing the simple wagon underframe I immediately set to work on improving the model and then ordered another test print. Here you can see the artist's impression (i.e. a nice rendering of the model) as well as the printed item (with it's fittings) which arrived yesterday.

For a first attempt at printing an entire wagon I'm really happy with the result; for example, the wheels fit perfectly in this version, as do the couplings into the NEM pockets, and while the printing process I chose to use (i.e. the cheapest one) doesn't allow for very fine detail the planks and bolts etc. are very well defined and haven't merged into one another. There are, however, a number of things I will need to tweak or add:

For a first attempt at printing an entire wagon I'm really happy with the result; for example, the wheels fit perfectly in this version, as do the couplings into the NEM pockets, and while the printing process I chose to use (i.e. the cheapest one) doesn't allow for very fine detail the planks and bolts etc. are very well defined and haven't merged into one another. There are, however, a number of things I will need to tweak or add:

- This model was printed before I'd figured out the brake gear so doesn't have any brakes at all.

- I forgot to add any doors, so unloading cargo would be tricky!

- Whilst the couplings fit perfectly into the NEM pockets, the pockets themselves are in danger of breaking off when you fit the couplings so I need to strengthen the way the pockets attach to the underframe.

- I miscalculated the width of the planks when building the model, so while there are seven side planks the printed item is only as tall as a five plank wagon.

- The buffers should be circular when viewed end on, but have ended up as vertical ovals. I think this is because I modelled them as a sphere which I crushed down almost flat, which resulted in the edges being quite thin. I'm guessing that when printed the vertical edges didn't bond properly. I'll probably fix this by modelling them as a thin cylinder.

Monday, January 21, 2013

Fixtures and Fittings

While I'm not going to pre-empt the wagon model I'm currently having printed, I thought I'd show you the fixtures and fittings that will be needed once the model arrives.

While there is no real need to model the track, wheels and couplings when designing the model, I found it helps give a better sense of scale. It might even have helped me realise that the axle holes were too small in the first test print as I would have been able to see that the wheels intersected the model rather than sitting freely in the axle hole.

These models aren't entirely accurate representations (for example the coupling is slightly more rounded) but their bounding boxes are correct which means that if the modelled part fits the real one will. For reference all three are Hornby parts; an R600 single straight track section, narrow NEM style couplings (part number R8219), and 12.5mm spoked wheels (part number R8098).

While there is no real need to model the track, wheels and couplings when designing the model, I found it helps give a better sense of scale. It might even have helped me realise that the axle holes were too small in the first test print as I would have been able to see that the wheels intersected the model rather than sitting freely in the axle hole.

These models aren't entirely accurate representations (for example the coupling is slightly more rounded) but their bounding boxes are correct which means that if the modelled part fits the real one will. For reference all three are Hornby parts; an R600 single straight track section, narrow NEM style couplings (part number R8219), and 12.5mm spoked wheels (part number R8098).

Saturday, January 19, 2013

In Good Company

I've recently spent some time (figuratively) crawling around under coal wagons inspecting their braking systems, in order to try and design a simple, but accurate, representation that I can add to my 3D printed underframe. One of the things I've discovered (two excellent resources are here and here) is that while the brakes on my model coal wagon worked so well that the wheels wouldn't turn, in real life they wouldn't have worked at all, as I fitted them the wrong way around.

By the late 19th century most wagons were fitted with a simple lever brake on one side only. The diagram shows the break lever (in red) in the off position. To apply the brake the lever was pushed down. This turns the shaft (blue) and connecting arm (green) clockwise, which in turn moves the two push rods and attached brake shoes (black) outwards and onto the wheels. As you can see this is a really simple, but effective, braking system. The one downside being that if you had to apply a brake to a run away wagon you might have to cross the track to get to it, which may well be bad for your health and well being!

The easiest way to solve this problem is to simply fit a completely independent brake system to the other side of the wagon, but with the brake lever always at the right hand end of the wagon (so it appears to always be in the same place no matter which side you view the wagon from). This means that when you view the connecting arms from one side of the wagon, the nearest turns clockwise while the one on the other side turns anti-clockwise as the brake is applied. This means of course that you can't simply connect the two brake systems together by extending the shaft (blue) the full width of the wagon.

To overcome this problem, and to allow either brake lever to be used to apply both sets of brakes requires a clutch mechanism (shown in yellow) and for the push rods and connecting arms to now be mirror images of each other. This works, because if you push down the far lever (which is the same as previously) then it now turns both connecting arms such that the push rods are forced outwards applying the breaks, but because of the clutch it has no effect on the other break lever. If, however, you push down on the near side lever then, via the clutch, it turns the shaft anti-clockwise applying the brakes on both sides.

Not only did I manage to fit the brake system wrong on the Parkside Dundas kits I built, but it appears that I'm in good company as neither Dapol or Hornby seem to model fully correct brake gear either.

Firstly, on the left, we have what I accidentally ended up modelling. Two independent brake systems, but with the connecting arms and push rods on the near side fitted the wrong way around. This means that instead of applying the brake when the near side lever is lowered, the brake shoes will actually move further away from the wheels, which clearly is wrong. Mind you, on the right, you can see how both Hornby and Dapol model the braking system. They go to the trouble of modelling the clutch to allow either brake lever to be used to operate both brakes, but then don't bother to model the wagon wide connecting shaft, completely negating the point of fitting the clutch mechanism. I'm assuming they don't bother modelling the connecting shaft because a) it is out of sight under the wagon and b) would possibly be quite fragile, but either way they clearly weren't aiming for accuracy.

So which version am I going to add to my 3D model? Well given that there will be no difference in cost, if I can work out a sensible way of modelling the clutch, then I'll probably model all three correct versions. This way I can print which ever I want depending on what time period I want them to represent. This is one of the main advantages of 3D printing over traditional manufacturing; there are no upfront cost to create expensive moulds, which allow us to print variations at no extra cost.

By the late 19th century most wagons were fitted with a simple lever brake on one side only. The diagram shows the break lever (in red) in the off position. To apply the brake the lever was pushed down. This turns the shaft (blue) and connecting arm (green) clockwise, which in turn moves the two push rods and attached brake shoes (black) outwards and onto the wheels. As you can see this is a really simple, but effective, braking system. The one downside being that if you had to apply a brake to a run away wagon you might have to cross the track to get to it, which may well be bad for your health and well being!

The easiest way to solve this problem is to simply fit a completely independent brake system to the other side of the wagon, but with the brake lever always at the right hand end of the wagon (so it appears to always be in the same place no matter which side you view the wagon from). This means that when you view the connecting arms from one side of the wagon, the nearest turns clockwise while the one on the other side turns anti-clockwise as the brake is applied. This means of course that you can't simply connect the two brake systems together by extending the shaft (blue) the full width of the wagon.

To overcome this problem, and to allow either brake lever to be used to apply both sets of brakes requires a clutch mechanism (shown in yellow) and for the push rods and connecting arms to now be mirror images of each other. This works, because if you push down the far lever (which is the same as previously) then it now turns both connecting arms such that the push rods are forced outwards applying the breaks, but because of the clutch it has no effect on the other break lever. If, however, you push down on the near side lever then, via the clutch, it turns the shaft anti-clockwise applying the brakes on both sides.

Not only did I manage to fit the brake system wrong on the Parkside Dundas kits I built, but it appears that I'm in good company as neither Dapol or Hornby seem to model fully correct brake gear either.

Firstly, on the left, we have what I accidentally ended up modelling. Two independent brake systems, but with the connecting arms and push rods on the near side fitted the wrong way around. This means that instead of applying the brake when the near side lever is lowered, the brake shoes will actually move further away from the wheels, which clearly is wrong. Mind you, on the right, you can see how both Hornby and Dapol model the braking system. They go to the trouble of modelling the clutch to allow either brake lever to be used to operate both brakes, but then don't bother to model the wagon wide connecting shaft, completely negating the point of fitting the clutch mechanism. I'm assuming they don't bother modelling the connecting shaft because a) it is out of sight under the wagon and b) would possibly be quite fragile, but either way they clearly weren't aiming for accuracy.

So which version am I going to add to my 3D model? Well given that there will be no difference in cost, if I can work out a sensible way of modelling the clutch, then I'll probably model all three correct versions. This way I can print which ever I want depending on what time period I want them to represent. This is one of the main advantages of 3D printing over traditional manufacturing; there are no upfront cost to create expensive moulds, which allow us to print variations at no extra cost.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Using Lasers To Build Wagons

While I'm really enjoying this whole 3D printing thing I wish there was a UK based printer I could use. I'm currently printing my items via Shapeways and while their printing prices are fairly reasonable (and seem inline with everyone else) there is a €9 posting and packing charge to add to each order. In fairness to Shapeways this seems a common delivery charge for most of the printers when delivering outside the county in which they are based. This charge means it isn't worth ordering a single small model, such as my TPWS grids, as the postage cost would far outweigh the cost of the model. So each time I've placed an order it has included a number of items, and this time was no different. As well as test printing the mini TPWS grids, I also made two other, more experimental, prints.

I've finally hit on an interesting idea for a layout, one that has even got Bryony interested in the planning, but there are a number of pieces of rolling stock that I'll have to build from scratch. One approach would be to attempt to build rolling stock from plasticard and brass wire etc. but given my success so far with 3D printing I thought I'd give that a whirl first. Printing complete wagons, or at least the major components, will have the advantage that once I can print one wagon I can print as many as I need without having to spend any extra time.

Given that I managed to assemble a Parkside Dundas wagon so that the wheels wouldn't turn, I decided that the hardest part would probably by designing the underframe in such a way that the wheels would fit and turn properly. So one of the prints in my latest order was a simple wagon underframe.

As you can see the wheels do fit, and I promise they do turn quite easily; when weighted appropriately (sitting the mostly full bottle of liquid gravity on it) I can easily push it around my layout. I am, however, going to alter the model slightly. If you look closely you can see that the wheels are actually bending the model outwards quite significantly.

The problem is that while the model is wide enough to take the wheels I didn't make the holes for the axle deep enough. I'm not sure if this is really a problem with my 3D model or with the printing process. All the previous items I've printed have been using Shapeways Frosted Ultra Detail material. This material allows for the smallest of details to be printed, down to 0.1mm, but is also quite expensive (it's the most expensive of the plastics they support). As I wasn't trying to model fine detail but was simply checking rough proportions I printed this model in the cheapest material: White Strong and Flexible. Rather than printing by depositing plastic from a print head, this material is turned into a model using a process known as selective laser sintering or SLS; essentially using a laser to fuse a powder together to form the model. While printing in this way is cheaper it has a much lower accuracy, ±0.15mm, than the Frosted Ultra Detail material, ±0.025, and I'm wondering if this has made the holes slightly shallower than I intended.

Anyway as a test print, to make the postage and package costs worthwhile, I'm more than happy with how it turned out and I'm already working on refining the model ready for the next print run.

I've finally hit on an interesting idea for a layout, one that has even got Bryony interested in the planning, but there are a number of pieces of rolling stock that I'll have to build from scratch. One approach would be to attempt to build rolling stock from plasticard and brass wire etc. but given my success so far with 3D printing I thought I'd give that a whirl first. Printing complete wagons, or at least the major components, will have the advantage that once I can print one wagon I can print as many as I need without having to spend any extra time.

Given that I managed to assemble a Parkside Dundas wagon so that the wheels wouldn't turn, I decided that the hardest part would probably by designing the underframe in such a way that the wheels would fit and turn properly. So one of the prints in my latest order was a simple wagon underframe.

As you can see the wheels do fit, and I promise they do turn quite easily; when weighted appropriately (sitting the mostly full bottle of liquid gravity on it) I can easily push it around my layout. I am, however, going to alter the model slightly. If you look closely you can see that the wheels are actually bending the model outwards quite significantly.

The problem is that while the model is wide enough to take the wheels I didn't make the holes for the axle deep enough. I'm not sure if this is really a problem with my 3D model or with the printing process. All the previous items I've printed have been using Shapeways Frosted Ultra Detail material. This material allows for the smallest of details to be printed, down to 0.1mm, but is also quite expensive (it's the most expensive of the plastics they support). As I wasn't trying to model fine detail but was simply checking rough proportions I printed this model in the cheapest material: White Strong and Flexible. Rather than printing by depositing plastic from a print head, this material is turned into a model using a process known as selective laser sintering or SLS; essentially using a laser to fuse a powder together to form the model. While printing in this way is cheaper it has a much lower accuracy, ±0.15mm, than the Frosted Ultra Detail material, ±0.025, and I'm wondering if this has made the holes slightly shallower than I intended.

Anyway as a test print, to make the postage and package costs worthwhile, I'm more than happy with how it turned out and I'm already working on refining the model ready for the next print run.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

The West Coast Fiasco

Even, if like me, you have little interest in modern diesel or electric locomotives (I'm a committed steam era person) you can't possibly have failed to hear about the fiasco surrounding the awarding of the franchise to run the West Coast main line -- unless of course you don't live in the UK. Lets just say it's been a disaster from start to finish that has left the government owing millions of pounds to a number of large railway companies and we still don't know who will end up running the line in the long run. If you want all the details then the BBC have a pretty comprehensive write up of the whole debacle.

Although there is currently no end in sight to the bidding process, there is now a new company interested in bidding for the franchise; Bigjigs Toys Ltd. It's nice to see that there are still a few people in government with a sense of humour.

Although there is currently no end in sight to the bidding process, there is now a new company interested in bidding for the franchise; Bigjigs Toys Ltd. It's nice to see that there are still a few people in government with a sense of humour.

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Just Because I Could

About a month ago I blogged about the Train Protection Warning System (TPWS) grids I'd had 3D printed in order to hide the light sensors I use as part of my scale speed trap. While these are tiny items (their bounding box is just 9mm x 13.12mm x 1mm), I decided, just because I could, to design a set of the smaller TPWS grids. These smaller grids are fitted to sidings, where the low speeds involved aren't conducive to the use of the full size grids (you get interference).

These mini buffer stop grids are really really small; their bounding box is just 9mm x 8.05mm x 1mm! Fortunately the tiny size isn't an issue for the 3D printing process involved and my test print was delivered today.

Those of you who have browsed around Penistone Railway Works, may well have been able to predict this blog post, as I'd listed these grids as "Coming Soon". Now that I've actually handled the printed model, if you are in need of some small TPWS grids, I'll happily sell you a set of four for a very reasonable price.

These mini buffer stop grids are really really small; their bounding box is just 9mm x 8.05mm x 1mm! Fortunately the tiny size isn't an issue for the 3D printing process involved and my test print was delivered today.

Those of you who have browsed around Penistone Railway Works, may well have been able to predict this blog post, as I'd listed these grids as "Coming Soon". Now that I've actually handled the printed model, if you are in need of some small TPWS grids, I'll happily sell you a set of four for a very reasonable price.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)